Los Angeles Times Local

Killing of chickens in Jewish ritual draws protests in L.A.

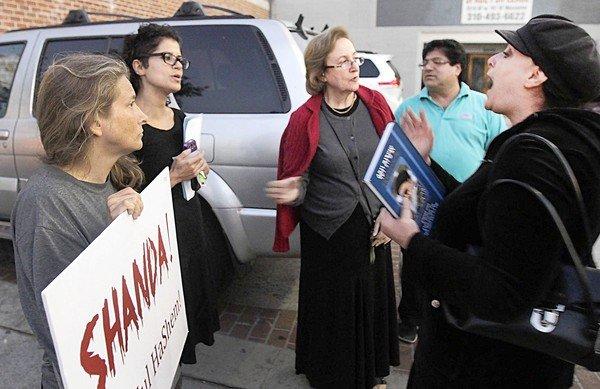

Protesters

debate with a woman, right, outside the Ohel Moshe synagogue on Pico

Boulevard in Los Angeles. Kaparot rituals have been held at the

synagogue's parking lot. (Lawrence K. Ho, Los Angeles Times / September 10, 2013)

Related photos »

Photos: The Jewish ritual of kaparot

Photos: The Jewish ritual of kaparot

By Martha Groves and Matt Stevens

September 11, 2013, 6:47 p.m.

In

a parking lot behind a Pico Boulevard building, inside a makeshift tent

made of metal poles and tarps, a man in a white coat and black skullcap

grabs a white-feathered hen under the wings and performs an ancient

ritual.

He circles the chicken in the air several times and

recites a prayer for a woman standing nearby whose aim is to

symbolically transfer her sins to the bird. The young man then uses a

sharp blade to cut the hen's throat.

In the days before

Yom Kippur,

the Jewish Day of Atonement, this ritual will be repeated untold times

in hastily built plywood rooms and other structures in traditional

Orthodox Jewish communities from Pico-Robertson to Brooklyn. Promotional

fliers on lampposts in this neighborhood advertise the kaparot service

at $18 per chicken or $13 apiece for five or more.

But the

practice is increasingly drawing the ire of animal rights activists, and

some liberal Jews, who say the custom is inhumane, paganistic and out

of step with modern times.

"An animal sacrifice in this day and

age?" said Wendie Dox, a Reform Jew and animal rights activist who lives

nearby. "That is not OK with me."

This year, activists have

launched one of the largest, most organized efforts ever in the

Southland to protest the practice, known variously as kaparot, kapparot

or kaparos.

Over the weekend, a coalition of faith leaders and

animal rights proponents held a "compassionate kaparot ceremony" during

which rabbis used money rather than chickens for the ritual, an accepted

alternative. Organizers say that more than 100 people attended and that

some stayed to demonstrate late into the night.

Read More Here

**********************************************************

PHOTOS: Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Kaparot ritual of swinging chickens over the head

Posted Sep 11, 2013

Swinging

chickens over the head is part of the Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Kaparot

ritual in the Ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv,

Israel,Wednesday, Sept. 11, 2013. Observers believe the ritual transfers

one’s sins from the past year into the chicken, and is performed before

the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish year

which starts at sundown Friday.

An

Ultra-Orthodox Jewish man swings a chicken over his head as part of the

Kaparot ritual in the Ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv,

Israel,Wednesday, Sept. 11, 2013. Observers believe the ritual transfers

one's sins from the past year into the chicken, and is performed before

the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish year

which starts at sundown Friday. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Ultra-Orthodox

Jews hold chickens as part of the Kaparot ritual in the ultra-Orthodox

city of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv, Israel, Wednesday, Sept. 11, 2013. (AP

Photo/Oded Balilty)

An

Ultra-orthodox Jewish man swings a chicken above his head during the

Kaparot ceremony in the central Israeli city of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv,

on September 11, 2013. AFP PHOTO/JACK GUEZ/AFP/Getty Images

An

Ultra-orthodox Jewish woman swings a chicken above her head during the

Kaparot ceremony in the central Israeli city of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv,

on September 11, 2013. AFP PHOTO/JACK GUEZ/AFP/Getty Images

**********************************************************

News

The

Euless

neighborhood is mostly quiet, a sleepy suburb of pleasant ranch-style

homes, winding creeks and mossy oaks that looks as if it could have been

plucked from any American city. Except, of course, for the ancient gods

that populate the home and religion of one of the area's most

controversial residents.

Brandon Thibodeaux

Jose Merced

Brandon Thibodeaux

Inside

Jose Merced’s shrine room, devotees of all ages participate in the

cleansing ceremony for Virginia Rosario-Nevarez as part of her seven-day

initiation into the Santería priesthood.

Brandon Thibodeaux

The

deities, or Orishas, communicate through cowrie shells, telling one

woman about her past, present and future in a divination reading.

Brandon Thibodeaux

A

Santería priest performs the cleansing ceremony on Nevarez (center)

before 60 or so deities, which sit in pots on the shelves to her left.

Brandon Thibodeaux

Money is part of the ritual offering to the Orishas during a cowrie shell reading.

But

Jose Merced

doesn't shy away from controversy—and he has no plans of doing so on

this crisp day in late September. No matter that his neighbors remain

uneasy with the ritual singing and drumming that are part of his

Santería religion; no matter that they might, as before, call the police

if they feared he was engaging in animal sacrifice; no matter that the

city of Euless, even after losing a drawn-out lawsuit that tested the

boundaries of religious liberty in Texas, is still searching for new

ways to shut down Merced's spiritual practices. For him, the deities who

reside in the back room of his house have been silenced long enough.

It's

been nearly three and a half years since he stopped the ritual

slaughter of four-legged animals in his home to pursue litigation

against the city over his right to do so. With a decision from the 5th

U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals

in his favor and against the city's health and safety concerns, Merced,

a flight attendant, will resume his full religious practices tonight.

As

the sacrificial hour approaches, several priests (Santeros) are

preparing the 40 assorted goats, roosters, hens, guinea hens, pigeons,

quail, turtle and duck who grow noisy and nervous in their cages. Their

lives will be taken in an exchange mandated by Olofi, Santería's supreme

god and source of all energy, to heal the broken body and spirit of

Virginia Rosario-Nevarez

and to initiate her into the Santería priesthood. No medical doctor has

been able to alleviate her suffering—the intractable back pain that

makes walking unbearable, her debilitating depression and loneliness.

During

a spiritual reading, lesser deities have told Merced that for Nevarez

to be healed, she must become a priestess. In the initiation ceremony

for priesthood, a high priest will sacrifice animals, which must die so

she can live a healthy and spiritual life. In a theology similar to

Christian grace in which Jesus died to forgive the sins of his

followers, the animals will be offered in sacrifice to Olofi and the

other deities (

Orishas), who will purge her of negative energy as she makes her commitment to them.

Mounted

against a wall in the back room shrine in Merced's house are shelves

containing clusters of small ceramic pots, ornately decorated and filled

with shells, stones and other artifacts—the physical manifestations of

the Orishas that reside in the room. To initiate Nevarez as a priestess,

new godly manifestations of the old gods on Merced's shelf must be

born. To make this happen, animal blood will be spilled onto new pots,

which the priestess will take home to begin her own shrine with her own

newly manifested gods.

Much of theology behind Santería's rituals

remains unknown to Nevarez, though more of its secrets will be revealed

to her as she grows in her commitment.

Secrecy defines the

Santería religion, which is why estimates, even by its own followers, of

the number of its U.S. adherents vary widely between one and five

million. The religion's clandestine nature was also a point of

contention during the lawsuit. At trial, the city asked Merced if its

health officials could witness a sacrifice to determine if it violated

Euless' ordinances prohibiting animal cruelty, the possession of

livestock and the disposal of animal remains, but Merced said only

initiated priests were permitted to see one. The exclusion of outsiders

stems from the long history of persecution Santería's followers

suffered. Santería came to Cuba from West Africa during the slave trade

centuries ago, a peculiar melding of the Yoruba religious traditions of

captured slaves and the Catholicism of their masters. Slaves were

forbidden from practicing their indigenous beliefs, so they hid that

practice from their oppressors, adopting the names of Catholic saints

for their Orishas (Saint Peter for Ogun, for example) whose divine

intervention they could call upon when seeking protection, health and

wisdom.

But tonight, Merced has had enough of secrecy. The

litigation has taken a toll on his physical appearance. He looks

heavier, grayer, worn out. The national media generated by the case,

however, has left him more comfortable with the presence of strangers in

his house, even with local news trucks parked in his front yard. And

this evening Merced is allowing his first nonbeliever to witness an

animal sacrifice.

"I'm going to let her see one and that's it," he

says, standing in front of a long, flowing curtain concealing the

entrance to his shrine. He is unwilling to listen to any who oppose the

outsider observing the ceremony. Some in the shrine raise their eyebrows

but return to the task at hand. They figure Merced's deities are in

control today. If he's allowing the Orishas to be seen by a nonbeliever,

then the gods must be OK with it.

Merced has recently disregarded

other premonitions of danger. Three days earlier in his home, he held a

séance for Nevarez in preparation for her priestly initiation. Ten

members, all wearing white, gathered inside his converted garage, now a

spare kitchen. On top of a white tablecloth sat a crucifix, prayer

books, pencils, paper and a fishbowl of water—there to cleanse the

spirits from negative to positive. Hanging on the wall were decorative

hollowed-out gourds, painted in primary colors to represent a handful of

the 60 or so Orishas in Santería. In one corner sat a life-size female

black doll dressed in a flowing skirt and bandanna, a half-empty bottle

of rum and lighted candles placed nearby.

One of the Santeros at

the table knotted his face, his expression troubled. He began to grunt

and take short breathes, acting possessed by the spirit, which came

alive through him and asked for some rum. A woman handed him a gourd

brimming with white

Bacardi. As he gulped the rum, he walked hastily toward Merced.

This

was a negative spirit, and it had a message: It would be best for

Merced to leave the area or send everybody away from his home and remain

alone.

Merced folded his arms defensively across his chest. Time

and again, throughout his legal troubles, lawyers, neighbors, friends

and even Santeros had proposed he do the same. Why didn't he just leave

Euless? Worship somewhere else? Why come out and create so much

controversy when he could just keep things secret and live in peace like

the others? To Merced, this spirit represented an insult to everything

he had accomplished.

"How dare you?" accused Merced, reminding the

spirit that it was "immaterial"—and in Merced's house. "I don't have to

go anywhere. I'm going to keep up the fight."

----

Jose Merced never intended to be the face of Santería in North Texas, although he might argue that it was his fate.

He grew up in

San Juan,

Puerto Rico, and recalls his childhood as happy and stable—that is,

until his father left the family. Merced, at 12, felt abandoned and grew

physically ill, developing a sharp, chronic pain in his stomach and

intestines. A medical doctor suggested exploratory surgery, but his

mother wouldn't hear of it.

She had grown up in a home where

regular séances took place between family members. When pregnant with

Jose, a stranger stopped her in a shoe store and told her she would give

birth to a male child on April 20 who would possess the gift of

spirituality. Merced was born on April 19 and early on became intrigued

with the spiritual realm.

After Merced became ill, he asked his

mother to bring him to a woman his mother had been seeing for private

spiritual readings. Even without him mentioning it, the woman told him

about his intestinal pains and his nightmares. Hoping she could cure

him, Merced began attending weekly séances at her home. Many of those

attending wore colorful, beaded necklaces, and he asked the woman how he

could get some. She told him those who wore the necklaces were

followers of Santería, and he could only get them when he needed them,

not when he wanted them. A year and a half later, she did a reading for

him with the deities of Santería and told him it was time.

At 14, he donned his

collares—necklaces

that represented the protection granted by the Orishas. For a short

while, Merced, who weighed 210 pounds, began to feel better, but it

didn't last. "Spirits also can bother you when you're not knowing or

understanding what it is you come in life to do," he now explains.

The

woman became his godmother in Santería, and she continued to treat him

with herbal potions and spiritual readings. Over the next 18 months, he

lost 60 pounds and had good months as well as bad.

Finally, Merced

says that the Orishas spoke through the woman and told her that the

only way to make his pain disappear was to get initiated as a priest.

Merced was ready, but the ceremony was expensive, $3,000, and he didn't

have enough money. For a year after graduating high school, Merced saved

up, working as a clerk for the Puerto Rico Department of Education in

San Juan. By early 1979, with his mother's help, he had saved enough

money, though he still had no idea what to expect.

He had helped

with other initiations at his godmother's house but was never allowed

inside the shrine-room. "I saw the animals going in alive and coming out

dead," Merced recalls. But he had no idea why. He helped by cleaning or

cutting up the meat or plucking chicken feathers. Sometimes he would

ask the people outside the room what was happening inside. "And when you

asked something, all they answered was, 'It is a secret.' If you're not

crowned [a priest], you're not supposed to know. So when I went in to

my ceremony, I didn't have a clue."

On the day of his initiation,

he was called inside the shrine and told to keep his eyes closed. Four

hours later, he was dressed in regal-looking robes, his head completely

shaven. Later he was told he had been possessed by his Orisha, but he

remembered nothing.

After the crowning ceremony, it was time for

the animal sacrifice. As the animals were brought in, he was told to

touch his head to the animal's head and its hooves to other areas of his

body. The animal was absorbing his negativity. He had to chew pieces of

coconut, swallowing the juice but spitting the coconut meat into the

animal's ear.

He would later learn that this was necessary for the

"the exchange ceremony," which came next. The pieces of coconut

represented Merced's message—his thoughts, feelings, needs—which were

transferred to the goat for direct passage to Olofi. His physical

contact with the animal was also symbolic of his commitment to God. As

soon as the animal's blood was spilled, Merced's negativity, which had

been absorbed by the goat, was released. The purified blood then spilled

into the pots.

Shortly after the initiation, he says his stomach

pains subsided. "I never, ever have felt again the same pain that I used

to feel before," he says.

Although he had little contact with his

father, a nonbeliever, he invited him to his divination readings two

days later. His father also visited him at his mother's house

immediately after the seven-day ceremony concluded. Merced was wearing

all-white, his head shaved clean, and his father insisted this was all

his mother's doing—she was the one who had become a priestess a year

earlier. His father demanded he end these religious practices and join

the

National Guard

like he had. Merced told him, no: He had become a priest for health

reasons, and he refused to let him shake his faith, particularly after

his father had been so uninvolved in his life for so long.

If his

father had learned anything from the divination readings, he would know

what the Orishas had in store for his son. The priest had told him he

would travel the world. He told him he would become a priest who would

initiate others. And he told him that people would have reason to

remember his name.

----

The

first year of his priesthood was a difficult one. At the department of

education, many of his co-workers would shoot him strange, even hostile

glances when he wore his necklace and dressed in the all-white attire

his religion required him to wear in the year following his intiation.

In

1989, he learned about a job opening with a commercial airline, and the

next year he began to work for the company in Dallas. The work was

good, but his spiritual life suffered.

He didn't know any Santeros

here and removed his necklaces to avoid drawing attention to himself.

"I didn't want people to know [about my religion]," Merced says. "That's

hiding. And I lived hiding for a long, long time."

A closet in

his apartment in Euless served as the shrine for his Orishas, which he

had brought in cloth bags when he first traveled from Puerto Rico to

Dallas.

A year after the move, he bought his first home and

dedicated an entire room to his deities. Using the Yellow Pages, he

located a botanica (a spiritual supply store) on West Jefferson and felt

brave enough to introduce himself as a Santero. Here he would find

others who shared his beliefs.

Over the years, he would become

godfather to at least 500 followers and initiate at least 17 priests. As

these new priests went out into the community and gave out necklaces to

their own godchildren, Merced's own house grew. He estimates that today

there are close to 1,000 believers in his Santería community.

As

Merced grew more confident in his job and in himself, he stopped hiding

his religion to outsiders and would tell them about it when asked. He

took the same approach in his personal life. And in 2002, when his

boyfriend, Michael, decided to take his last name, their commitment to

each other seemed a natural progression. "This is me," Jose says. "And

everyone will accept me for what I am."

In 2002 Merced moved into

the house he currently owns in Euless, but it wasn't until 2004 that he

started attracting the attention of the authorities. On September 4,

Euless police and animal control officials showed up unannounced at his

home. An anonymous caller had complained that goats were being illegally

slaughtered in his backyard. When the authorities arrived, Merced was

in the middle of a sacrificial ceremony inside his shrine. The police

told him to stop—that if he didn't they would fine him or arrest him.

But the animal control officer intervened: Merced was allowed to

continue the ritual and would not be arrested, at least not that day.

Read More Here

**********************************************************

Great Cuba documentary

pj689

Uploaded on May 15, 2007

Scenes from 2005's "Havana Centro" by Paul Johnson. Rare scenes of a Santeria ritual taking place in Havana, Cuba

**********************************************************