Ancient brains turn paleontology on its head

- Date:

- November 9, 2015

- Source:

- University of Arizona

- Summary:

- When scientists presented evidence of an ancient, fossilized brain a few years ago, it challenged the long-held notion that brains don't fossilize. Now, seven new specimens have been unearthed, each showing traces of neural tissue from what was undoubtedly a brain.

A:

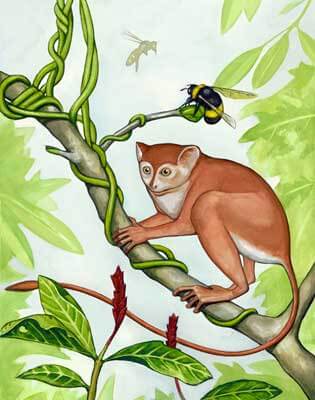

Under a light microscope, the above fossil shows traces of preserved

neural tissues in black. B: An elemental scan of this fossil uncovered

that carbon (in pink) and iron (in green) do not overlap in the

preserved neural tissue.

Credit: Strausfeld et al. and Current Biology

Science

has long dictated that brains don't fossilize, so when Nicholas

Strausfeld co-authored the first ever report of a fossilized brain in a

2012 edition of Nature, it was met with "a lot of flack."

"It

was questioned by many paleontologists, who thought -- and in fact some

claimed in print -- that maybe it was just an artifact or a one-off,

implausible fossilization event," said Strausfeld, a Regents' professor

in UA's Department of Neuroscience.

His latest paper in Current Biology addresses these doubts head-on, with definitive evidence that, indeed, brains do fossilize.

In the paper, Strausfeld and his collaborators, including Xiaoya Ma of Yunnan Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology at China's Yunnan University and Gregory Edgecombe of the Natural History Museum in London, analyze seven newly discovered fossils of the same species to find, in each, traces of what was undoubtedly a brain.

The species, Fuxianhuia protensa, is an extinct arthropod that roamed the seafloor about 520 million years ago. It would have looked something like a very simple shrimp. And each of the fossils -- from the Chengjiang Shales, fossil-rich sites in Southwest China -- revealed F. protensa's ancient brain looked a lot like a modern crustacean's, too.

Using scanning electron microscopy, the researchers found that the brains were preserved as flattened carbon films, which, in some fossils, were partially overlaid by tiny iron pyrite crystals. This led the research team to a convincing explanation as to how and why neural tissue fossilizes.

In another recent paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Strausfeld's experiments uncovered what it likely was about ancient environmental conditions that allowed a brain to fossilize in the first place.

The only way to become fossilized is, first, to get rapidly buried. Hungry scavengers can't eat a carcass if it's buried, and as long as the water is anoxic enough -- that is, lacking in oxygen -- a buried creature's tissues evade consumption by bacteria as well. Strausfeld and his collaborators suspect F. protensa was buried by rapid, underwater mudslides, a scenario they experimentally recreated by burying sandworms and cockroaches in mud.

This is only step one. Step two, explained Strausfeld, is where most brains would fail: Withstanding the pressure from being rapidly buried under thick, heavy mud.

To have been able to do this, the F. protensa nervous system must have been remarkably dense. In fact, tissues of nervous systems, including brains, are densest in living arthropods. As a small, tightly packed cellular network of fats and proteins, the brain and central nervous system could pass step two, just as did the sandworm and cockroach brains in Strausfeld's lab.

"Dewatering is different from dehydration, and it happens more gradually," said Strausfeld, referring to the process by which pressure from the overlying mud squeezes water out of tissues. "During this process, the brain maintains its overall integrity leading to its gradual flattening and preservation. F. protensa's tissue density appears to have made all the difference."

Now that he and his collaborators have produced unassailable evidence that fossilized arthropod brains are more than just a one-off phenomenon, Strausfeld is working to elucidate the origin and evolution of brains over half a billion years in the past.

"People, especially scientists, make assumptions. The fun thing about science, actually, is to demolish them," said Strausfeld.

His latest paper in Current Biology addresses these doubts head-on, with definitive evidence that, indeed, brains do fossilize.

In the paper, Strausfeld and his collaborators, including Xiaoya Ma of Yunnan Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology at China's Yunnan University and Gregory Edgecombe of the Natural History Museum in London, analyze seven newly discovered fossils of the same species to find, in each, traces of what was undoubtedly a brain.

The species, Fuxianhuia protensa, is an extinct arthropod that roamed the seafloor about 520 million years ago. It would have looked something like a very simple shrimp. And each of the fossils -- from the Chengjiang Shales, fossil-rich sites in Southwest China -- revealed F. protensa's ancient brain looked a lot like a modern crustacean's, too.

Using scanning electron microscopy, the researchers found that the brains were preserved as flattened carbon films, which, in some fossils, were partially overlaid by tiny iron pyrite crystals. This led the research team to a convincing explanation as to how and why neural tissue fossilizes.

In another recent paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Strausfeld's experiments uncovered what it likely was about ancient environmental conditions that allowed a brain to fossilize in the first place.

The only way to become fossilized is, first, to get rapidly buried. Hungry scavengers can't eat a carcass if it's buried, and as long as the water is anoxic enough -- that is, lacking in oxygen -- a buried creature's tissues evade consumption by bacteria as well. Strausfeld and his collaborators suspect F. protensa was buried by rapid, underwater mudslides, a scenario they experimentally recreated by burying sandworms and cockroaches in mud.

This is only step one. Step two, explained Strausfeld, is where most brains would fail: Withstanding the pressure from being rapidly buried under thick, heavy mud.

To have been able to do this, the F. protensa nervous system must have been remarkably dense. In fact, tissues of nervous systems, including brains, are densest in living arthropods. As a small, tightly packed cellular network of fats and proteins, the brain and central nervous system could pass step two, just as did the sandworm and cockroach brains in Strausfeld's lab.

"Dewatering is different from dehydration, and it happens more gradually," said Strausfeld, referring to the process by which pressure from the overlying mud squeezes water out of tissues. "During this process, the brain maintains its overall integrity leading to its gradual flattening and preservation. F. protensa's tissue density appears to have made all the difference."

Now that he and his collaborators have produced unassailable evidence that fossilized arthropod brains are more than just a one-off phenomenon, Strausfeld is working to elucidate the origin and evolution of brains over half a billion years in the past.

"People, especially scientists, make assumptions. The fun thing about science, actually, is to demolish them," said Strausfeld.

Story Source:

The above post is reprinted from materials provided by University of Arizona. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

The above post is reprinted from materials provided by University of Arizona. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

- Xiaoya Ma, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Xianguang Hou, Tomasz Goral, Nicholas J. Strausfeld. Preservational Pathways of Corresponding Brains of a Cambrian Euarthropod. Current Biology, 2015; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.063

Cite This Page:

University

of Arizona. "Ancient brains turn paleontology on its head: Strongest

evidence yet that it's possible for brains to fossilize and, in fact, a

set of 520-million-year-old arthropod brains have done just that."

ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 9 November 2015.

<www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/11/151109083905.htm>.